Chapter 14

The Final Pass

I spent my final day in the Himalayas crossing the Mesokanto La (5330m), a remote pass that links Tilicho Lake with the Kali Gandaki Valley, just to the north of the Annapurna Range.

After recovering in Kathmandu for a few days after the Everest hike, I relocated to Pokhara and began to focus on the Annapurnas, ticking off routes which will be familiar to anyone who's hiked in Nepal: Poon Hill, Annapurna Base Camp, Mardi Himal, and finally the Annapurna Circuit. These are well worn trails, and I hiked them at a comfortable pace, doing my best to savour my last few weeks in the mountains. After months of hiking, dramatic views have become completely normalised, but every now and then I'd be struck anew by the beauty of the valley, especially in the soft afternoon light of early December. From different parts of the circuit, the peaks of Manaslu, Dhaulagiri, and of course Annapurna were all visible, each at the summit of their own majestic massifs.

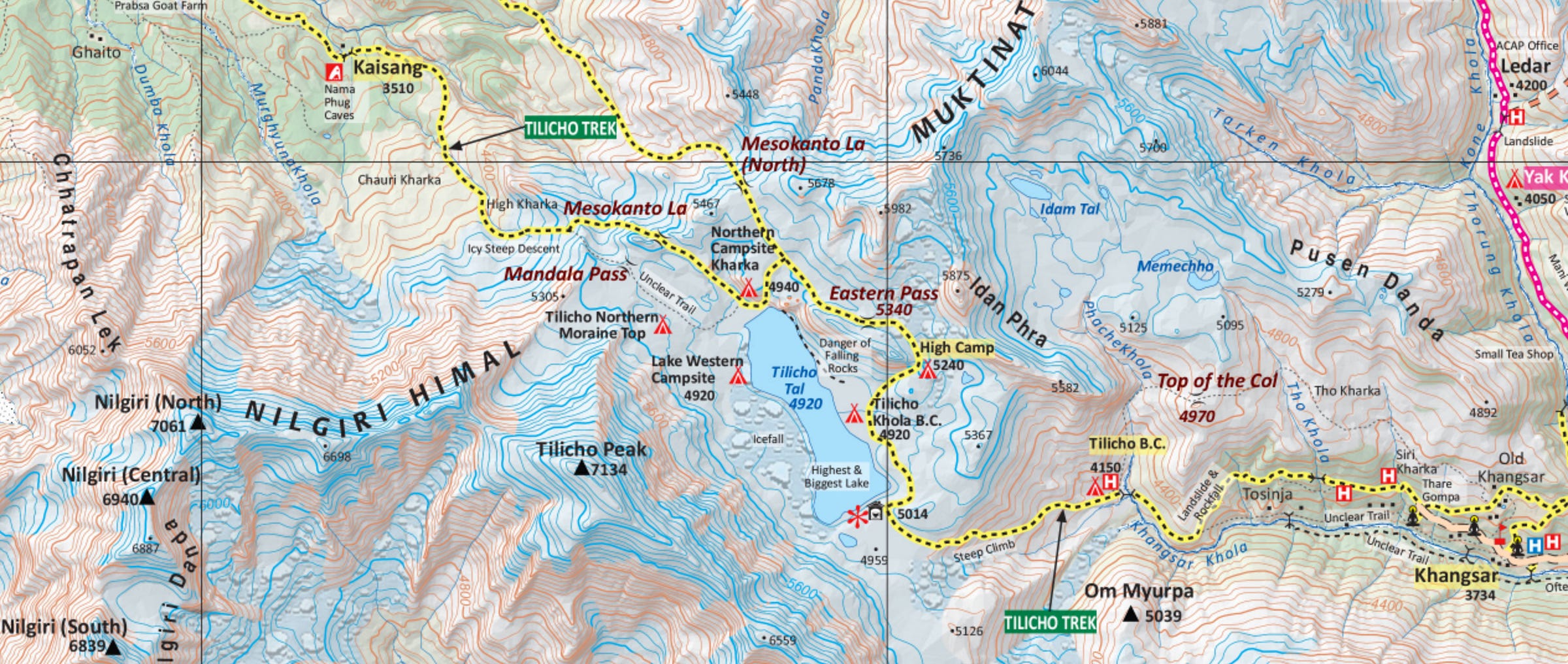

The standard way to end the Annapurna Circuit is by crossing the Thorang La (5416m), a pass linking the town of Manang with Muktinath, a pilgrimage site home to an ancient Vishnu temple. It's a serious pass (and was the site of the 2014 disaster), but it remains well travelled, with regular teahouses and plenty of hikers and guides all year round. The Mesokanto La, which sits a few miles to the south, is much more remote and less visited, and I decided this would be a more fitting end to my time in Nepal. Had I had company, it would've been just another big mountain day, similar to dozens of others I've had this year. But solo, and with no prospect of phone signal, it felt like a more consequential undertaking. The last teahouse is at Tilicho Lake Base Camp, and from there it's over 30km of rugged high altitude terrain to the next place where you can stay, the village of Thini. Between those two points, seeing another hiker was unlikely, at least once you pass the popular viewpoint at Tilicho Lake, and so the route requires total self sufficiency.

The idea of hiking it solo and in a single push made me nervous. So much so, that I wanted my research to be exhaustive, leaving as little as possible to chance. My first step was to speak to some of the trekking agencies in Pokhara, but as is typical when suggesting an ambitious itinerary, I was told it was impossible, and that the route would take at least 3 days (requiring me to carry a tent). Another guide conceded that it could be done in a single push, but looked me up and down skeptically when I said I would be attempting it solo, warning me that the route is 'very dangerous', then regaling me with a story, already familiar to me, of an ill-fated Thai trekking group who lost two members attempting the pass in 2022.

I had more luck online, uncovering a detailed trip report from a German team who hiked the pass about 20 years ago, and a few more useful pieces of beta from a forum for Himalayan hikers. The main quandary was deciding on the route, for there are actually two adjacent passes. The 'northern' pass sits at a slightly higher altitude, but has a more gradual descent off the other side. The 'main' pass a couple of kilometres to the south is lower, but has a steeper and more treacherous north-facing decent, which spends most of the day in shadow. In snowy conditions, guides use ropes to lower their clients down the steepest part. To safely navigate it without gear, I'd need the slopes to be fully scoured of snow.

I left for the Annapurna Circuit with only a vague commitment to the pass, psychologically hedging in various ways: I told myself I would only attempt it if the weather was perfect, if I felt strong, and if I got some reliable updates on ground conditions from locals at Tilicho Base Camp, who would be best placed to know. A few days before I reached the pass, I called Manav to discuss the route with him. He was in Maharashtra, about to set off on a month long traverse of the Sahyadris, and we spent half an hour or so discussing the minutiae of the route. We agreed that the crux was the descent off the pass, and that I'd have to leave early enough that I could still turn around and retreat back to Base Camp before sundown if it was too dangerous. We also arranged an informal alert system – Manav's friend Shubrank would be on call, and if he didn't get a message from me to say I was safely in Thini by the evening, he would raise the alarm.

Slightly reassured, I spent the next few days hiking towards Tilicho, overtaking a few end-of-season hiking groups, and enjoying absolutely perfect December weather, not a cloud in the sky. After a comfortable stay in Manang, I left the main valley and watched the landscape slowly transform into the lunar high alpine that characterises much of the Great Himalayan Range. I was the only guest at the teahouse in Tilicho Base Camp, and I spent the evening huddled around the stove with the proprietor. He insisted that I should head for the main pass, as the trail is much better defined and easier to follow. He also informed me that the previous season, locals had improved the trail on the other side, so while it was still a difficult descent, it would be a safer option that trying to find the northern pass alone. I took his advice.

I went to bed early, setting an alarm for 5.15am, but lay awake for a few hours with the nervous anticipation a long mountain day always seems to bring. It was bitterly cold, and it took me a while to warm up in my sleeping bag. After a few hours of sleep, the alarm sounded, and I went into autopilot mode, quickly dressing and packing my bag. I had spent weeks thinking about this route, and now the time for thinking was over. It was time to do. After a swift breakfast of porridge and black coffee, I filled two litres of water, put on my head torch, and left into the frozen dawn.

I could see a steady stream of lights ahead of me on the hillside, from hikers who would be going to Tilicho Lake before returning to base camp. I used each group as a target, slowly catching and overtaking them in turn, trying to move fast but without spiking my heart rate on the steep switchbacks. The sun rose just before I reached the top, illuminating the valley in bright light. After cresting the hill you arrive at the edge of a huge plateau, where after a few minutes the brilliant blue water of Tilicho Lake creeps into view, enclosed by mountains on all sides. At the edge of the lake, I exchanged pleasantries with a few hikers as they snapped photos, and stopped to do the same. We were no longer sheltered from the strong winds whipping off the lake, and even exposing my hands for a few moments left my fingers numb. My water bottles had both turned to slush.

And then I was alone, heading north along the shore towards a saddle some maps refer to as 'Eastern Pass'. I tried to concentrate, placing my feet carefully between the loose rocks, and even more so as I crossed the first frozen stream, leaping between boulders to avoid the slick ice. Tilicho Lake sits just below 5000m, and I was now ascending steeply. Over the last month, the strong acclimatisation I'd built in the Everest region had been slowly dwindling, and the week I'd spent resting in Pokhara prior to leaving for the Annapurna Circuit had been the final nail in the coffin. I felt weak and I moved slowly, dutifully shuffling up the steep shoulder that led behind a ridge to the north of the lake. Once I reached the top, I could see the Mesokanto La on the horizon, but it still looked awfully far. I'd hoped to reach it within 5 hours, but this deadline slipped away as I navigated the faint trail, my feet crunching the scree beneath me, with every small uphill grade slowing me to a crawl. Finally, just before noon, I arrived at the cairns and prayer flags that mark the top, and allowed myself a few moments to appreciate the view back towards Tilicho, and then northwards to Mustang and Tibet, before nervously peering down the other side.

The descent was steep, probably 45 degrees or more, but I could see a trail and no snow. So far so good. I inched my way down, but on each corner of the switchbacks were large patches of black ice, so I had no choice but to go around them, using a combination of hands and trekking poles to gently lower myself down the slope. After a tense few minutes, the grade eased and I was back on firm ground, with only a long, winding descent of almost 3000m between me and the safety of the valley floor.

The route was mostly straightforward, the only obstacle being large frozen streams which occasionally intersected the trail. I wasn’t carrying spikes, so I had to follow them downstream to where they were small enough to jump over. After a couple of hours, I came across the first signs of human habitation, passing some abandoned stone shelters, and then a small hamlet with two or three farmhouses, where a couple of locals were out collecting dung for the fire. I asked for water, and they pointed me to a hose where I could fill my long-empty bottles. After another two hours meandering down dusty sheep trails, I reached Thini around 4pm, just under ten hours after leaving Tilicho Base Camp. I sat in the village square, exhausted, first texting Shubrank to let him know I had safely arrived, and then pouring out little mounds of sand from my shoes. A family walked past, and the young boy (as they often will to tourists) asked me if I had any chocolate. I handed him my last Snickers, put my shoes back on, and followed them down the lane in search of somewhere to stay.

The next morning, I had to drag my tired body out of bed to catch the 6am bus from Jomsom back to Pokhara, and as we rattled down the Kali Gandaki Valley I couldn’t help craning my neck out of the window to look at the faint lines on the mountainside. Infinite trails, stretching off into anonymous little side valleys, valleys which would take other years, and maybe other lifetimes to explore. But this year was over. In a few days, my Nepal visa would expire, my bank account would be empty, and I would be returning to the quotidian concerns of life back in the UK. And so this will be the concluding post of Mountains of Things, at least until I can plot my return to the mountains, and have another journey to tell you about. But there will be other journeys. The trails are infinite, and walking them is a lifelong pursuit.

Had fun reading pete!

Thank you, Pete, for describing amazing journey to the Himalayan Mountains. Enjoyed reading all your posts.